Managerial practises and e-scooter sharing services: pilot results

In one of my last post about e-scooter sharing services, I’ve informed you that it is not only the popularity of e-scooter sharing services, which is rising, but the emergence of the new vehicles at public space comes along with new challenges. In the previous post, I’ve also shown some examples of how various cities across Europe are trying to deal with the new challenges.

The new challenges are connected with urgent issues like missing legislation or safety on the streets, but also the question of how to ensure the new mobility service is effectively embedded into current urban and transport landscape.

Observing what is happening around this topic resulted in the research I’m currently conducting with my colleague for the Urban Policy Observatory. In this research, we have decided to:

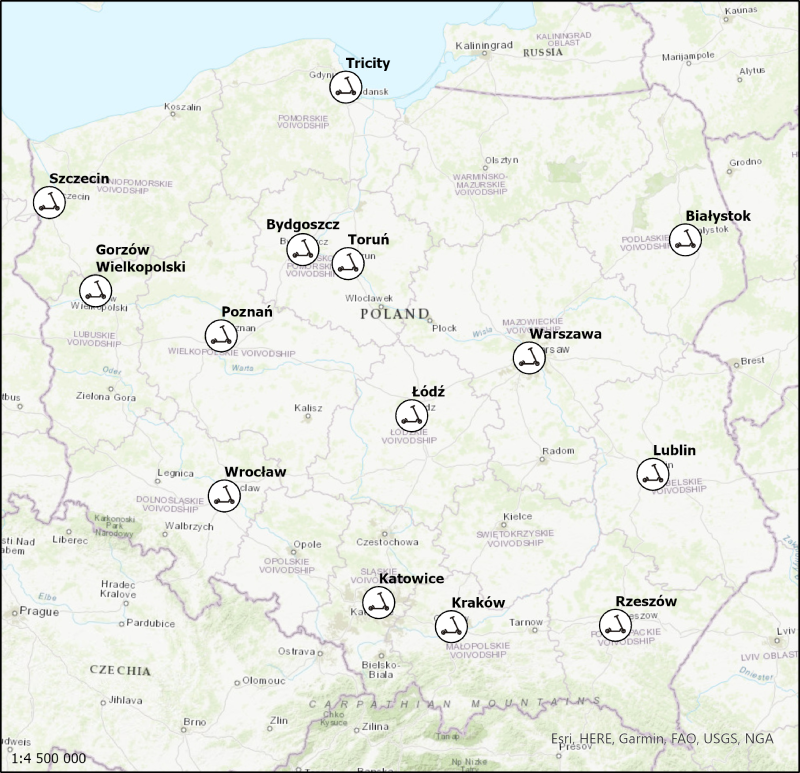

- map the coverage of e-scooter sharing schemes starting at the May 2020 (time when the covid-19 restrictions were slowly abolished)

- analyse the managerial practices of public authorities with e-scooter sharing scheme operators

While the survey about the managerial practises is still on, our article on the coverage of the e-scooter sharing schemes in Polish voivodeship capital cities has just been published in Data in Brief.

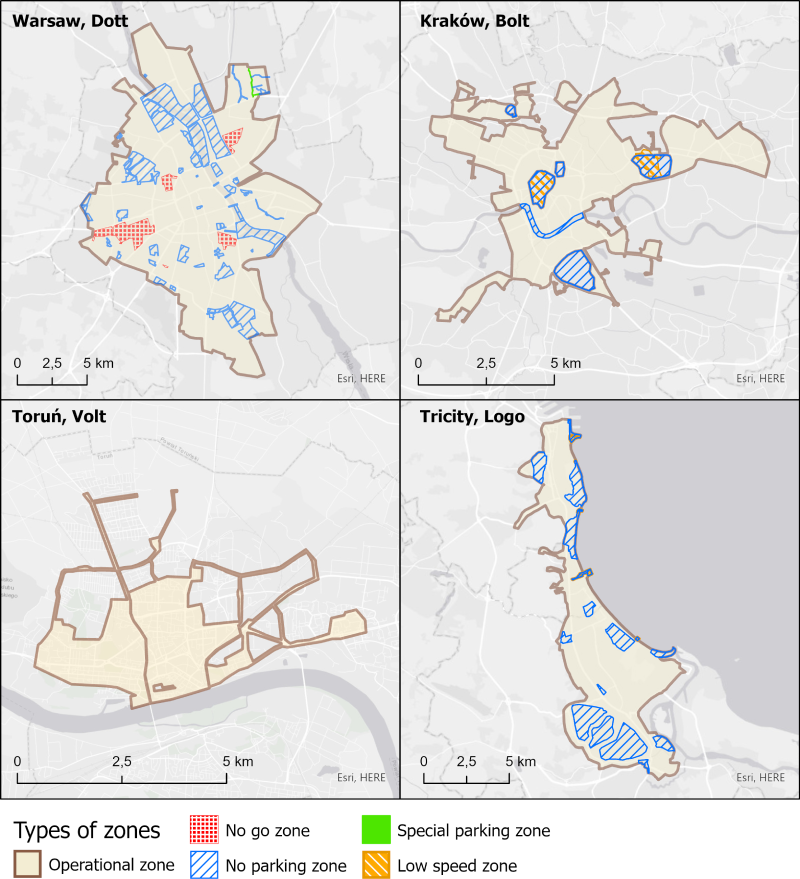

The article’s main goal was to identify which e-scooter sharing schemes operators function across the selected cities and zoom into the single neighbourhoods.

And why is this important?

Without knowing the geographical locations and the size of operational zones of e-scooter sharing schemes at the neighbourhoods level, it is impossible to understand whether the practice supports the proclaimed premises before e-scooter sharing schemes where implemented. For example, are they implementing the e-scooter sharing schemes all over the city as a last-mile solution or are they instead focused on highly exposed locations at the cities like old towns, centres and similar alike?

Thus, the data available in our repository could be of high value for transport and urban scientists or policymakers who focus on transport accessibility, micro-mobility solutions, transport sharing schemes, urban planning, and spatial management issues. For example, it is the question of accessibility, which is crucial for the transport planning authorities to, prevent from social exclusion or to understand the transport options in a given area.

The pilot study in Cracow suggests that currently the access to the e-scooter sharing services is unequally distributed across the Cracows urban area. Even though 6 operators offer (back at the end of summer) their services in Cracow. This means that the availability of e-scooter sharing services is a result of market competition between operators that want to penetrate the attractive locations only, than a coherent joint strategy of public authorities and operators over the integration of e-scooters with the rest of the transport system.

Such a state is clearly in the conflict with the proposed last-mile solution and sustainable mobility paradigm — keywords highly present at the marketing strategies but miles away from practical implementation.

This brings me to the notion of Beaten, who claims, that:

Sustainable transport vision leads to the further empowerment of technocratic and elitist groups in society while simultaneously contributing to the further disempowerment of those marginalised social groups who were already bearing the burden of the environmental problems resulting from a troubled transport system.”

Unfortunately, in our case, the sustainable transport vision is present only in the discourse over the role of-escooter sharing services which has not been fully imprinted into real actions. Under such a state, following John Adams Could technology save us?:

- The mobile wealthy and the immobile poor live in different worlds. The poor are confined by their lack of mobility in prisons with invisible walls.

A systematic strategy that would focus on mentioned issues might help overcome the unjust access to the e-scooter sharing schemes and the urban land. Unfortunately, our pilot shows that it is complicated for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, there is missing legislation which would define the critical competencies, responsibilities and rights of public authorities and e-scooter sharing schemes operators.

Secondly, the gaps in monitoring. Although the city officials meet with operators when necessary (the subject is mainly incorrectly parked scooters, less often their destruction), they no longer have information about the size of each service provider’s fleet and their served area in the city. Such data should be at the disposal of the authority as a basis for the conceptualisation of future strategies.

Further development needs to understand the cooperation between e-scooter sharing schemes operators and public authorities. Main barriers and motivations of the public and private sector in urban and transport development should be well known. Our research is going to shed some light on this matter.